Beskrivelse

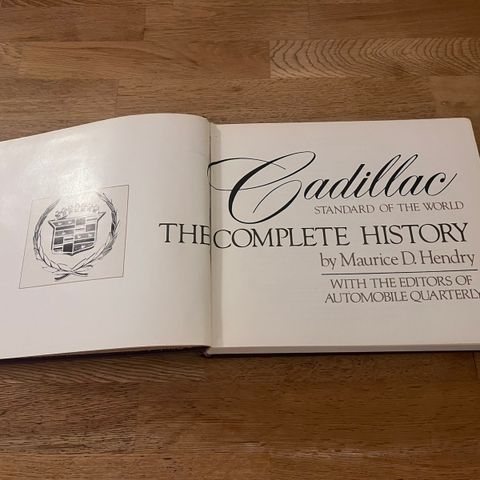

Cadillac. Photographs by Stephen Salmieri Hand-Painted by Sydnie Michele Salmieri; Text by Owen Edwards. Rizzoli. Hentes i Oslo eller sendes.

My father never had a Cadillac. In one way or another it marked him, and us, since the symbolic power of that particular car was such that not having one—in the fifties, in a town of green lawns and elm-lined streets forty-five minutes from Wall Street—meant as much as having one. Among my friends, knowing whose family had a Cadillac and whose didn't was essential information, like knowing who was Catholic.

We were prosperous enough to own a Cadillac, or at least optimistic for a future of limitless possibilities, which was a kind of prosperity. The act of going into debt to buy even the most far-fetched car was an expression of hope and a commitment to a country that had weathered depression and was and ended up owning the bright horizon; to drive home in an new Cadillac was as righteous as tithing the church, and as patriotic as saluting the flag. What was good for General Motors was good for America, said our Secretary of Defense, and few doubted he was right.

We did, once, veer close to making what was for American car buyers the ultimate choice. Toward the end of the war, we owned a black four-door La Salle, a '36 or '37, its rear window decorated with our A gasoline ration card. As reward for good behavior, I was sometimes allowed to ride into town standing on the running board, G-Man style, my arm crooked around the post of the wing window. Those were days when there were giants in the driveway. More than anything else about the car, its great pachyderm mass stays in my memory. Like our quiet, boundless neighborhood, like my father, the machine was reassuringly large, and magisterially protective. The La Salle, though produced throughout its fourteen-year history by Cadillac Motors, always kept a separate identity. Auto historians consider this a contributing factor to its mysterious lack of success, but it may well have been the reason my father bought one. No matter what its heritage, it was not a Cadillac. How my father could afford the car, even used, I can't understand; the Depression years had been a movable famine for him, and his credit can't have been much good; but he had managed to buy it, and I suspect that what the car was not meant more to him than what it was.

The La Salle was not reintroduced after the war, and in 1947 or so my father embarked on his determined path of non-Cadillac ownership, driving home one bright spring day in a dark blue Chrysler. Then came a Mercury convertible, and a series of Buick convertibles reaching its dramatic crescendo in a lumbering green Dynaflow Roadmaster.

It's too late to ask my father why we didn't have a Cadillac, but I think I can guess. For him, there must have been only two kinds of people who owned Cadillacs: those who were well-off, as the cozy suburban saying had it, and those who wanted to look better off than they were. To be the former might be a matter of time, and luck. To be the latter was unthinkable, contemptible, "typical" (a word which invariably expressed disapproval when uttered with a short shake of the head and upturned eyes). So we fell into a family lifetime of letting the rest of America lust after the car called—by the company that made it and the company it kept—the Standard of the World. To make exaggerated claims for a product is probably the oldest tradition in merchandising. Anything from motor oil to snake oil can be called the standard of the world—it is the kind of fundamentally ambiguous term beloved of advertising copywriters. But for the claim to have any weight at all, a manufacturer must do one of two things: either create a product that truly is the best, or assemble resources of size and strength sufficient to outlast or overwhelm the competition and become the standard by default. From time to time, by one or the other of these strategies, combined with an unwritten and mysterious recipe of ingredients that represents the witches' brew of the manufacturing process, a given product does, in fact, become undeniably the standard.

On rare occasions, it may even become something that represents far more than the fact of its existence or the range of its usefulness, evolving into a touchstone, a near-magical thing that serves our psyches as admirably as our practical needs. It is then that a product becomes not just the standard of the world, but the standard by which we judge our well-being. All manufacturers dream of this unexplainable consecration; the best companies work with that goal in mind, if only as unspoken hope. But no one has ever figured out how to make it happen, and when it does, no one can ever quite understand the reason why.

Whatever its merits or flaws as an automobile, the Cadillac is one of these material touchstones, perhaps the most potent that American industry has ever produced. Much has been written about the symbolism of the car in America, and even the most blatantly rhapsodic tracts are not completely implausible. Uniquely, the automobile is both the charger on which we ride in search of the grail, and the grail itself: conveyance and destination at the same time.